This post is the first of a mini-series on Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs), the latest phenomenon to hit higher education here in the US and internationally.

MOOCs are the most exciting thing to hit higher education since the personal computer became ubiquitous. Not everyone will agree, as the ongoing MOOC debate seems to have polarized the education community. But let’s think for a moment about the real underlying intention behind MOOCs: to provide increased access to quality education to an unprecedented number of people. Can anyone really argue with the inherent goodness of that premise? The link between economic growth and education has been proven time and time again. Knowledge leads to innovation, education leads to increased income, increased income leads to a larger taxation base, more resources lead to more public services and so on and so on. MOOCs have the potential to become the ultimate leveler in increasing access and decreasing the cost of education. So why are many shunning MOOCs? The reason is that many people simply don’t understand them, and struggle with embracing models that do not align with traditional educational paradigms.

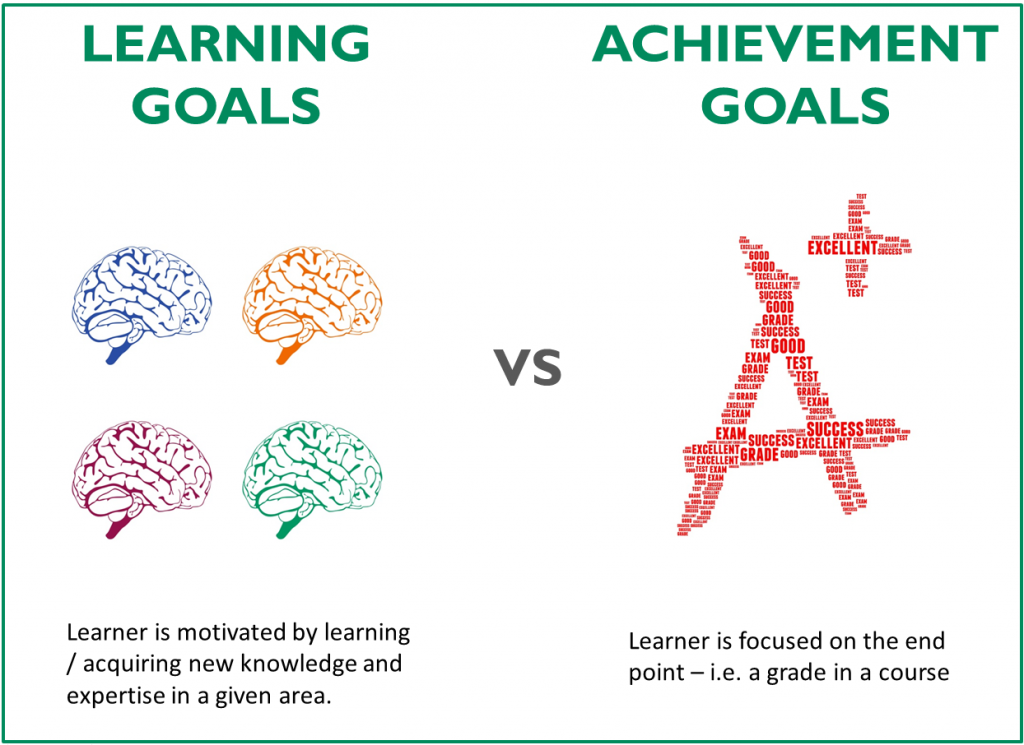

MOOCs are a relatively new phenomenon, and in some cases, they are being judged against a very old standard. Traditional educational models dictate that the instructor is at the center of education, and that learning is something that must take place within the confines of a set term, with the underlying goal being to master content in order to pass a rigid assessment in order to earn some form of credit. In the traditional model, linear pathways for learners are crucial, and every part of the learning experience functions in a self-contained microcosm. We associate learning with the Carnegie Unit / credit hour where learning is time-based. We attach a value to learning in the form of a grade to determine if the learner understands everything they need to know about a given subject area. This is an example of a ‘performance goal’. But what happens when the learner’s objectives are different than those of the traditional models? That is, what happens when students are more focused on simply learning than earning a letter grade (i.e. ‘learning goals’)?

Part of the criticism of MOOCs, of course, is that completion rates are low, and that they largely don’t lead to formal certification that ‘means’ anything. While current MOOC completion rates are low, I believe they shouldn’t be judged harshly for this. Many learners like Lucia are using MOOCs for their own practical and performance-driven needs. I don’t believe that non-completion negates the underlying power of the MOOC experience to drive real learning that can improve someone’s quality of life.

While Lucia is a fictitious MOOC participant, I have talked to many individuals who are using MOOCs for the their own reasons: one colleague who has enrolled in a finance course in order to increase her financial acuity, one student who has enrolled in a MOOC as a supplementary instructional tool, and on and on (and yes, I too have enrolled in a MOOC or two and am a non-completer).

Another scenario, of course, is that someone takes a MOOC and actually completes the entire course of study. Most students who complete a MOOC are offered some form of certificate. While it remains to be defined how employers will largely react to MOOC certificates as a form of credential, it is clear that institutions are increasingly looking to grant credit for outside courses completed online. Reportedly, some states are looking at legislation that would require public colleges to grant credit for faculty-approved online courses successfully completed outside the institution. As MOOCs and other forms of self-paced student directed learning evolve, we are likely to see additional legislative and policy change across the nation.

Where MOOCs are going, and what shape they will take on in mainstream education remains to be seen….I’ll pose a few thoughts on this in later blog posts. But for now, I encourage readers to keep in mind the inherent power of open education in evolving the way we think about learning, and the way we measure learning. Frankly, I encourage people to enroll in a MOOC (or two) to see what they are all about. To try something new, to learn something new, and to think about the possibilities. Always Learning.

Stay tuned for my next post on MOOCs right here on the Teaching & Learning Blog.