A recent Inside Higher Ed article dives into the challenges facing institutions following the rise of competency based learning (CBL). With the realization that seat time is less indicative of student success and as practical knowledge-attained takes the center-stage, the question arises: what happens to commonly held ideals about accreditation and the sacred credit-hour? While it’s not a new conversation, and these details must be worked out at the institutional level, it’s certainly worth exploring the value of CBL.

At the core of the CBL shift lies the question: are the decisions we’re making right for the student? In thinking beyond just the degree, we can start to view education more holistically and to see that the cycle of learning continues into employment and beyond (at Pearson, we call this “Always Learning”.) It is, of course, in the best economic and competitive interest of local communities, and more broadly, the U.S., to have an educated and informed workforce. When we view education as a holistic endeavor, we can determine the real value that students should be taking away from their college experience. And then we see that, at the macro level, big-picture competencies like critical thinking ability, problem-solving skills, and practical (vs. just theoretical) knowledge are key to ensuring our graduates have the requisite skills to succeed in the workplace and become productive citizens. And to me, CBL is about just that: changing the educational paradigm to put the student’s actual (not just perceived) needs first.

When describing what CBL means, I like to use the analogy of the student who wants to become a phlebotomist. He studies all of his requisite curriculum, learns about units of measure, drawing blood, and how to prepare the arm, etc. He studies, passes his course, and goes to work as a phlebotomist. On his first day on the job, he goes to draw a patient’s blood, and jams the needle into the arm, making his patient scream in pain. Well, if you don’t learn how to apply the knowledge you’ve obtained, what good will it do you? While this analogy is somewhat whimsical, it illustrates the importance of both ‘to know and to do’ which is germane to CBL. I like to say that CBL is about being able to “show you know and proving that you can do it.” Specifically, the way we look at CBL is this:

Competencies need to come from clearly identified and valid sources. These include:

- Professional Organizations

- Licensing Boards

- Experts in the Field

- Course and Program Outcomes

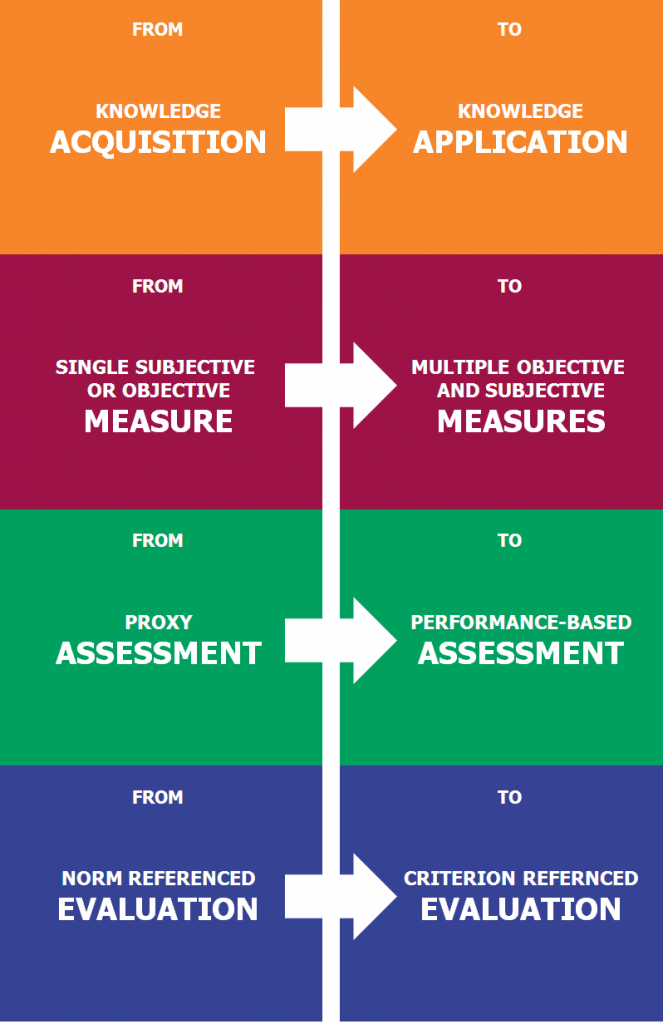

Once the competencies have been defined, CBL should consist of a series of transitions as outlined in the image below:

At the micro level, CBL works to hone in on tiny, fractional, research-tested competencies which, once accumulated, will lead to a holistic and deep understanding of a given subject. Designing courses around these competencies is complex, and involves a detailed analysis of how knowledge should be measured, and what really needs to be assessed. This is where the science of learning design plays a critical role, and this is where we believe the magic happens.

Rather than viewing the educational paradigm shift behind CBL as just another trend, I urge educators to focus on the inherent benefits of what some might say is disruptive innovation and focus more on the value it provides to our students. I believe that within a few years, CBL, and student-centric models of education in general, will be widespread. Those educators and institutions that are early adopters of this innovation can be proud that they play a role in a groundbreaking new movement that seeks to promote the real end-goal of higher education: the long-term success of the student.